The Chatbot Architecture of Tomorrow – (1) Setting the Stage

Chatbots present the illusion of artificial general intelligence, but do they have the potential to be vibrant thinkers? (Image created with DALL·E 3)

It’s been said that 2023 was the year of the chatbot, which is like saying that 1984 was the year of the personal computer and 1989 was the year of the internet. More is obviously on the way, but what will it look like? This is the start of a 3-part series of posts that will lean heavily on the academic literature to assess where things are, where they’re going, and what it may take to overcome current limitations on the reasoning ability of chatbots.

The basic framework of transformer neural networks was introduced in 2017, and is at the heart of the new generation of AI tools that have taken the world by storm. Transformers are behind language models like ChatGPT and have been broadly implemented for other modalities such as image generation and speech recognition. (think DALL-E and Whisper) Just over a month ago, the (admittedly doctored) demo video for Gemini Ultra blew people away as a demonstration of human-like audiovisual processing and cognition from a “natively multimodal” model.

1. So what’s wrong with the status quo?

Despite the recent chain of breakthroughs, there’s reasonable doubt as to just how powerful transformer-based models can be, and whether they truly present a path to human-like intelligence. Chatbots are frequently characterized as “stochastic parrots” that patch phrases together without really understanding what they mean. A number of academic papers have attempted rigorous formulations of this question, and sentiments have been evolving over the last year. For example:

Oct. 2022, Saparov et al.: “LLMs are quite capable of making correct individual deduction steps, and so are generally capable of reasoning, even in fictional contexts.”

Dec. 2022, Webb et al.: “large language models such as GPT-3 have acquired an emergent ability to find zero-shot solutions to a broad range of analogy problems.”

Sept. 2023, Lu et al.: “We find no evidence for the emergence of reasoning abilities [within LLMs]”

Jan. 2024, Gendron et al.: “Our results indicate that Large Language Models do not yet have the ability to perform sound abstract reasoning … the tuning techniques that improved LLM reasoning abilities do not provide significant help for abstract reasoning.”

The kicker is that these papers don’t even disagree with one another – they present experimental results addressing highly nuanced questions. Chatbots have fundamentally different cognitive hardware and software than humans do, which means that they may not apply the skill set you expect when tackling a familiar problem.

In particular, chatbots lean heavily on pattern matching. One might expect this from the ‘stochastic parrots’ analogy, but the underlying capability goes further. They can match or exceed human performance on text-based versions of the Raven’s Progressive Matrices, a popular test of fluid intelligence in which one needs to identify the rules that govern a pattern.

The downside is, chatbots have much less of a brain than humans do and often lack an internal model of the systems that they talk about. For example, if you try to play chess with a chatbot by typing in your moves, it tends to respond with a mishmash of brilliant and nonsensical play. It can reproduce moves from games that it was trained on but does not understand the layout of the chessboard – information best represented graphically – and so has no way to deal with novel positions.

2. Bigger models are no longer the answer.

Well, not the whole answer. Prior to 2023, the golden road to superior AI seemed to lie in scaling laws identified by OpenAI and others that relate model size and performance. However, the picture has become more nuanced as priorities for chatbot performance have become clearer, and are weighed against mounting dollar costs for training and operating the models. As OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said in April, 2023, “I think we’re at the end of the era where it’s going to be these, like, giant, giant models, and we’ll make them better in other ways.”

There are now numerous examples of well-trained smaller models outperforming larger ones, and it’s quite difficult to draw a line distinguishing model capabilities that are truly emergent with size and out of reach for a small model. Smaller models are also cheaper to run and can even be less expensive to train to a given level of performance, so long as you have enough training data and don’t hit a fundamental limit along the way:

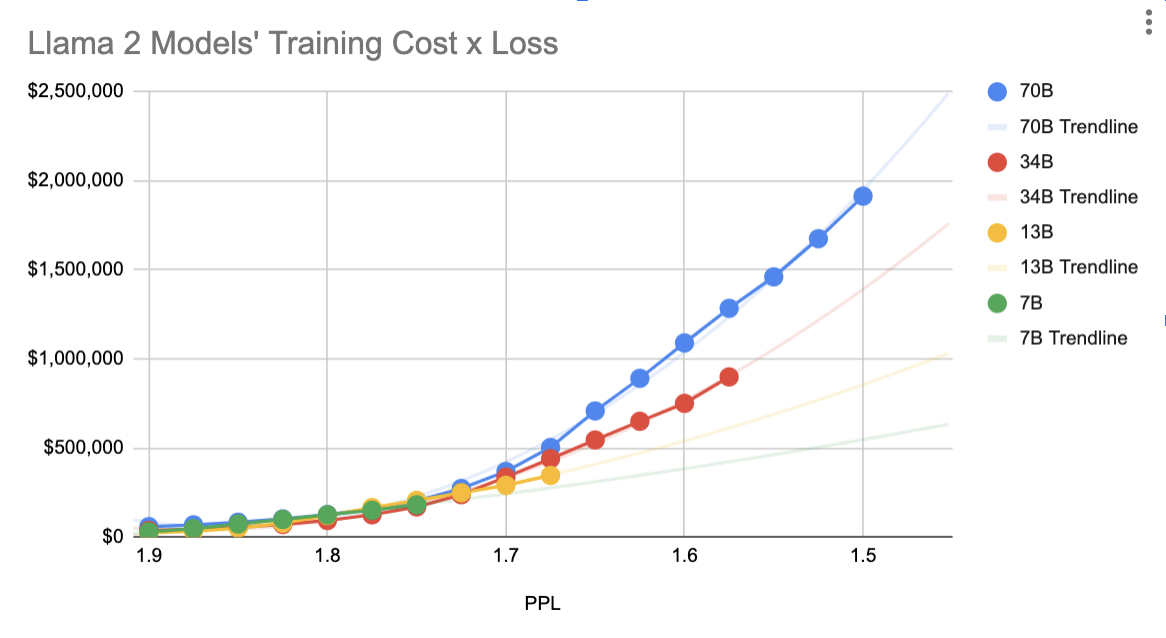

Figure 1: Smaller models can deliver better performance for the same training cost (evaluated here). Lower numbers are better for prediction accuracy, which is presented as training loss (perplexity, PPL). Dollar numbers on the vertical axis are estimated and should be a considered as a proxy for computing time (flops).

When GPT-3 first came out, it was a common refrain of op ed pieces that chatbots were still too small to think: the human brain has a factor of ~>1000 more synapses than GPT-3 has model parameters (175 billion model parameters). This turns out to be a very difficult comparison to really flesh out, not least because biological brains and AI transformer stacks have very different architectures (more on that later in this series!). However, I think if one frames things more carefully, it actually leads to the opposite conclusion: chatbot model size may be in the right ballpark for human-like cognition.

For example, the kind of reasoning behavior we want from chatbots is mostly associated with the human cerebral cortex, which only contains ~20% of the brain’s neurons. Even within the cerebral cortex, most regions have sensory/motor/etc associations with dubious relevance to a chatbot with no physical body. Bear in mind that the brain/body mass ratio is often more closely associated with intelligence than a creature’s neuron count. Orcas have more than twice the cerebral cortex neuron count of humans, but if there’s an arms race to recruit them into ‘thinktanks’, it’s heavily classified. Biological neurons also have noisy signal propagation and binary-like output, factors that cut into the per-neuron efficiency of analog computing systems. They need to manage their own training, which involves auxiliary neuronal systems for memory formation. These elements alone would reduce the synapse/parameter ratio to ~10 if each were treated as a factor of 2 penalty.

Still, size does matter, and larger chatbot models tend to be meaningfully smarter. They can memorize a larger fraction of the information in their training data before overfitting sets in. They’re capable of longer chains of internal logic, and can store more information within their state vectors:

Figure 2: Estimated number of tokens that can be stored in a state vector for models of different sizes (method and context here). The current sweet spot for open models (7B to 70B parameters) is highlighted. Model size is assumed to be proportional to the cube of model dimension, as for the GPT 3 and Llama 2 model families.

The current sweet spot for the size of freely downloadable ‘open’ chatbot models (Llama 2, Mistral/Mixtral, etc.) is 7B to 70B parameters, reflecting the limitations of consumer hardware. Quantization and pruning can compress these models to roughly half that size in bytes (7B parameters = 3.5 GB of memory) before performance loss becomes excessive.

3. A quick review of what chatbots do

Architecturally speaking, chatbots have one trick that they use over and over again:

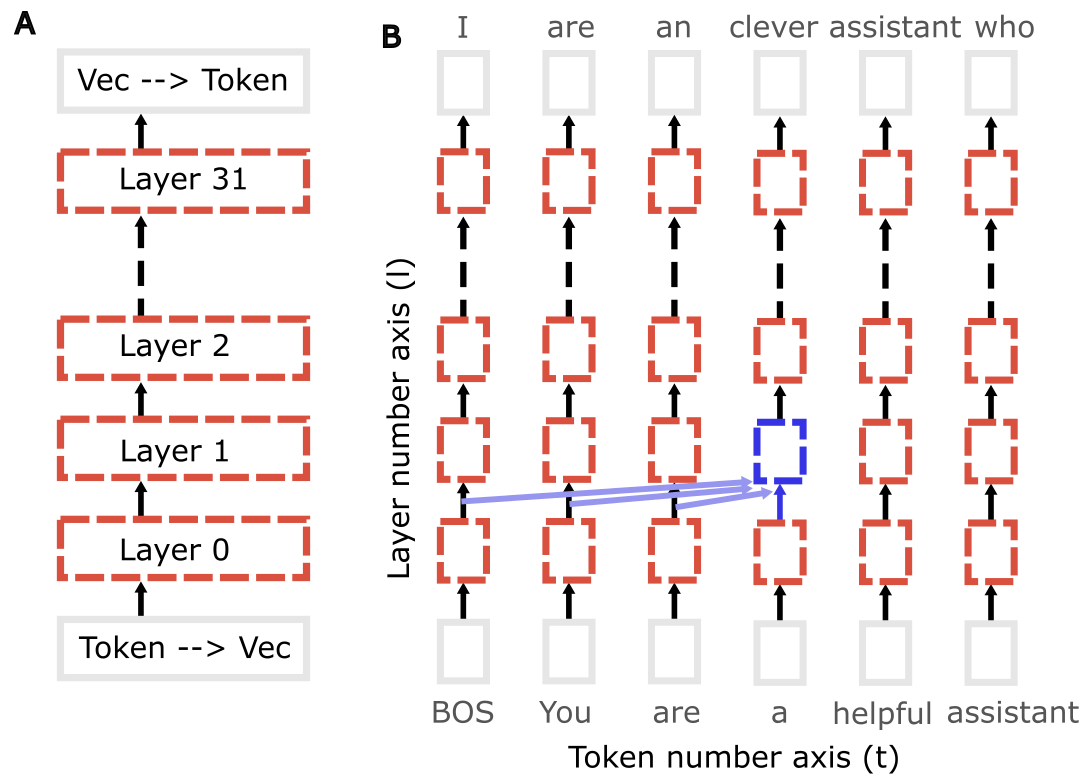

Figure 3: Architecture schematic of the 32-layer Llama 2 7B chatbot model. A, Black arrows represent the 4096-element ‘state vectors’ that are modified sequentially by each layer. B, An illustration showing words entered into the chatbot at the bottom of the transformer stack, and next-word predictions at the top of the stack. I’ve selected single-token words (“BOS You are a helpful assistant”) so that each word corresponds to exactly one set of state vectors. “BOS” is a dummy token placed at the beginning of all prompts. Blue arrows illustrate that each transformer has access to the output from all transformers in the previous layer up to its token position: the transformer output F(l,t) at token ‘t’ and layer ‘l’ can be described as a function of the transformer ouputs F(l-1, t’<=t).

- The text they’re working on is converted into tokens (about 0.75 tokens/word).

- The model acts on the tokens in order. First, the current token is converted into a high-dimensional vector (containing dmodel~5000 numbers for current language models). I’ll refer to this as the “layer 0 state vector”.

- The layer 0 state vector is passed into a transformer neural network layer that includes 2 sequential parts. The first part is the attention module, which accesses level 0 state vectors of previous tokens. The attention module can identify patterns within the state vectors and copy information forward into the current token location. The second part of the transformer is a 2-layer perceptron termed a “feedforward” layer.

- The output of the first transformer layer is the “layer 1 state vector”. This vector passes in exactly the same way through ~50 more transformer layers. Typically, the first ~1/3rd of these layers conduct a lot of memory recall. Output is refined in the 2nd half of the network. The last few layers purge the model’s memory of all the ‘thinking’ (memory recall, word association, etc.) that it conducted.

- The output layer, a roughly 30,000×5000 matrix, is used to convert the final state vector (let’s call it “layer 50”) into a list of possible output tokens and associated probabilities. This probability distribution is sampled to get a proposed output token.

- If the model is reading input from a user, then the output token is ignored. If the model is generating text, then the output token is added to the token list and will be the next token the model works on. In either case, we loop back to step #2.

- The model halts when a predetermined stopping condition is satisfied, at which point any tokens the model has output are converted to regular text. If a user is chatting with the model, a common stopping condition would be that the model has finished its reply and output the cue for the user to enter text. (Something like “\n\nUSER: ”. If you don’t stop it at this point, the model will happily continue to generate text and hold a 2-sided conversation with itself.)

In spite of the digital computer hardware that language models are run on, the models themselves are fundamentally analog, consisting of continuous functions acting on continuous variables. This means that if we want to think about the limits of chatbot cognition, a good starting point is to think of it as an analog computer and parse out its processing capabilities.

In analog computers, information is stored in vectors that hold continuous real number values rather than discrete-valued bits/bytes. These vectors are acted on by a series of ‘gates’ that transform the vectors via linear and nonlinear mappings. The weight matrices and activation functions within each transformer layer constitute a collection of gates.