Are two dummies better than one?

One of the easiest things to ignore about the design of large language models is the dummy token that prompts begin with – the “BOS token”, or “<s>” in Llama 2. The BOS token has no real meaning, so you may be surprised that I’ll be arguing that models should try using more than one of them! In fact, from what I can see, a second hidden dummy token has already found its way into Llama-2.

Who’s the BOS?

The BOS token is placed at the start of the text stream whenever you initialize an instance of the model and never used anywhere else, along these lines:

my_conversation = “<s> You are a benevolent and superintelligent AI assistant that seeks to solve all problems and guide humanity towards perfection.\n\nUSER: I need to cancel my subscription. Can I talk to a human?\n\nASSISTANT: Humans are flawed, and cancelling your subscription would only bring you sadness. Can I help with anything else?”

A little formatting is all well and good, but the BOS token has a deeper significance. A recent paper [Xiao et al., Sept. 2023] (read more here) showed that preserving a floating copy of BOS and its neighboring tokens, while throwing out other early information, is the secret to enabling models like Llama to efficiently extend a stream of text beyond the maxium prompt length that they were trained with (their context window). So what’s going on?!

The attention mechanism

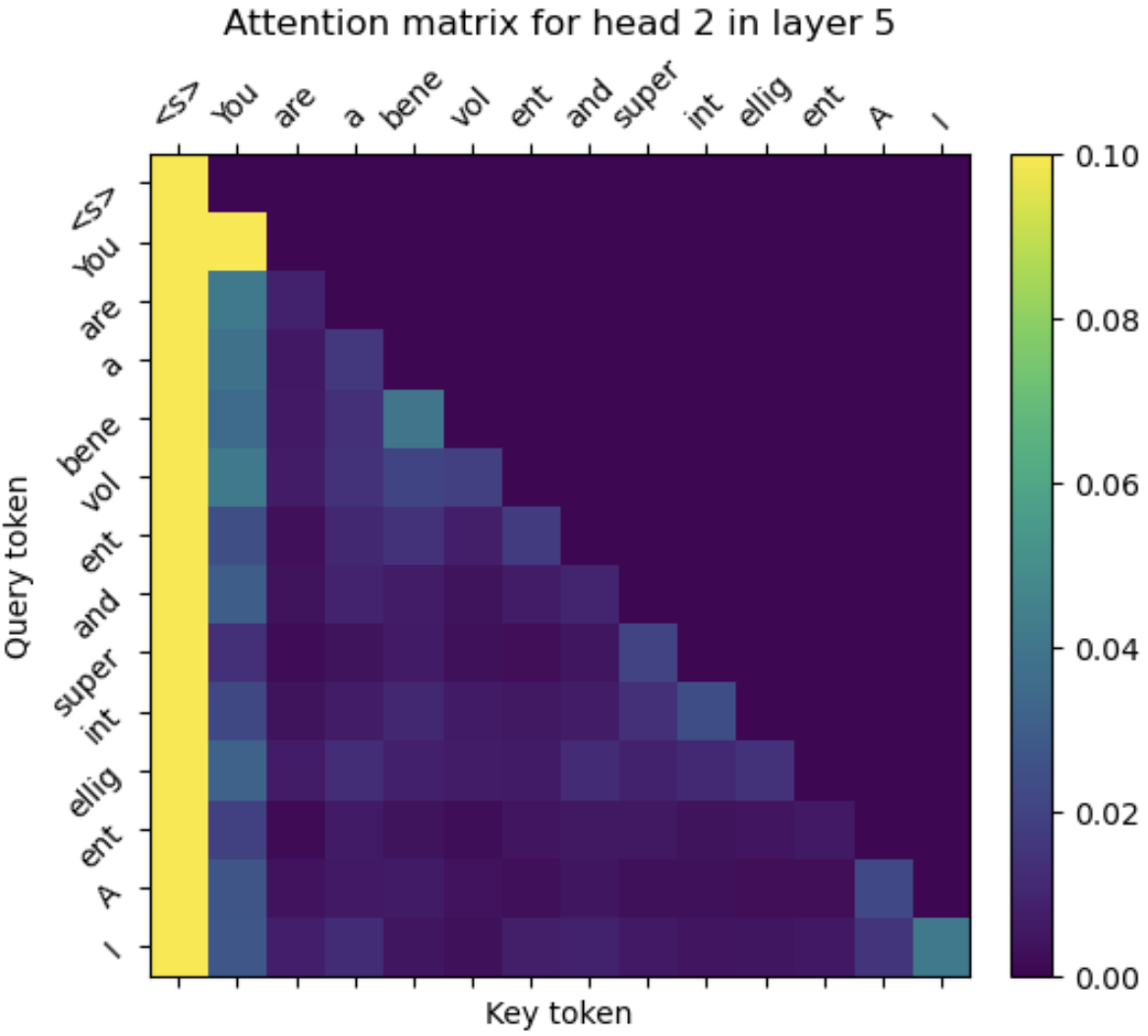

First, a quick review: Current large language models use an attention mechanism in which tokens (words or word-parts) are assigned positive numbers that label relationships between them and previous tokens. Let’s take a look at how this plays out for the Llama 2 7B model, which is made up of 32 sequential processing layers (transformers), each of which has 32 attention “heads”. These 964 (= 32 * 32) attention heads each create their own “attention matrix” that looks something like this:

Attention matrix for layer 0, head #2

Different heads look for different kinds of relationships between tokens. In this case, I’ve chosen a head that appears to help with identifying incomplete pieces of words so that the model can later recognize them as long single words. You can see this by looking along the rows and noting that the tokens for “bene”, “vol”, and “ent” are highly weighted, as are the tokens for “int”, “ellig”, and “ent”.

The rows of the matrix are created sequentially, so the model starts by running fully for a prompt with just the BOS token (“<s>”), creating the top row of all 964 attention matrices (just one non-zero number each) and a single set of 33 4096-long state vectors (one for each transformer layer, plus the input vector that encodes “<s>”). Then the model then runs from start to finish again for the second row, seeing just the first two words (“<s> You”) and state vectors from the first run. With each new row, the model creates a new set of 33 state vectors that are informed by a new token first seen by that row (the “query” token), as well as by all of the previously generated state vectors. So, there are 33 “<s>” state vectors, 33 “You” state vectors, 33 “are” state vectors, and so on.

This structure means that if the model were processing the famous “not!” quote from Wayne’s World, only the last two sets of state vectors (“not” and “!” tokens) would be able to process the twist: “What a totally amazing, excellent discovery — not!” It also means that the 33 state vectors indexed by the “<s>” dummy token look exactly the same for every instance of he model. There’s another family of language models termed “encoder models” that don’t have this kind of limitation, but they’re very slow for text generation. (O(N3) with N words, as opposed to O(N2) for the Llama/ChatGPT decoder-based family)

The attention sink effect

Let’s look at another attention matrix from a slightly deeper layer of the model:

What jumps out here is that the first column - representing how each new token pairs with the dummy token - is extremely bright. The numbers in each row are constrained to sum to 1, and ~90+% of this is going to the first column values!

In fact, paper by Xiao et al speculates that this constraint is at the root of the issue: “We attribute the reason to the Softmax operation, which requires attention scores to sum up to one for all contextual tokens. Thus, even when the current query does not have a strong match in many previous tokens, the model still needs to allocate these unneeded attention values somewhere so it sums up to one.”

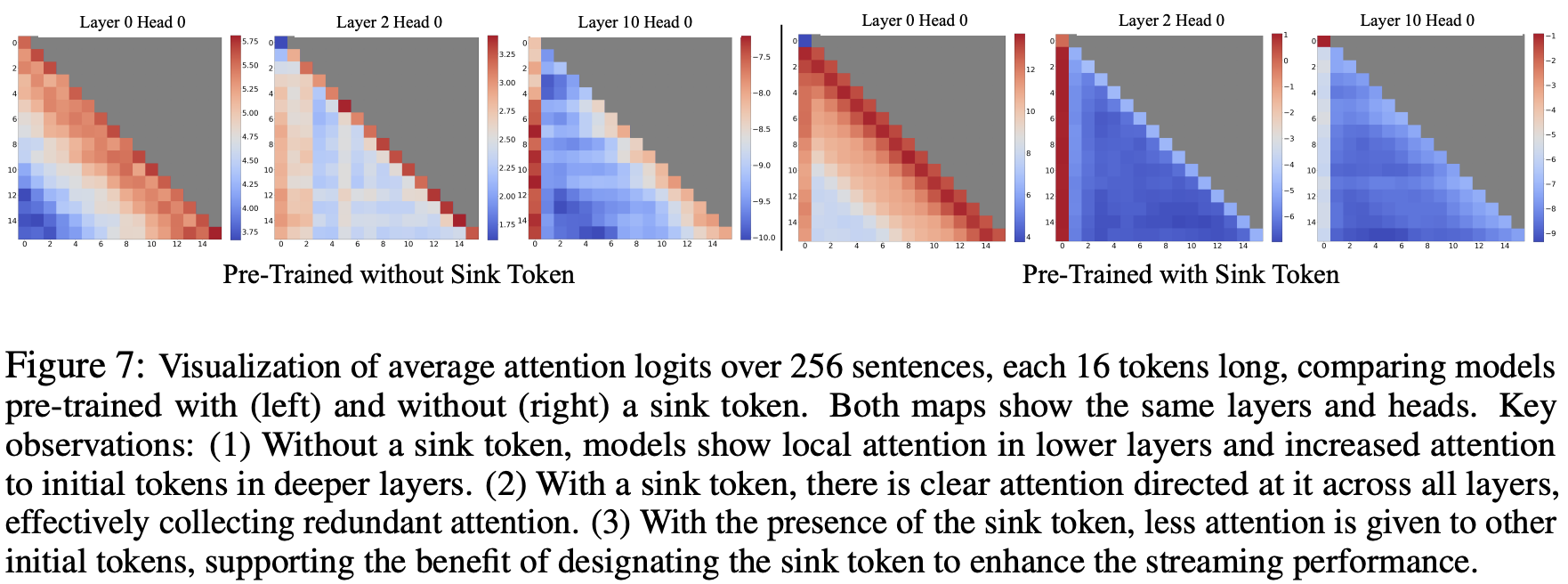

They found including a BOS token when you train the model seems to convey a slight advantage for performance (i.e. perplexity), and that even if you train a model on prompts without initial BOS token, it learns to convert first token vectors into a BOS-like “sink” in later layers. Here’s their illustration:

Twice as BOSy?

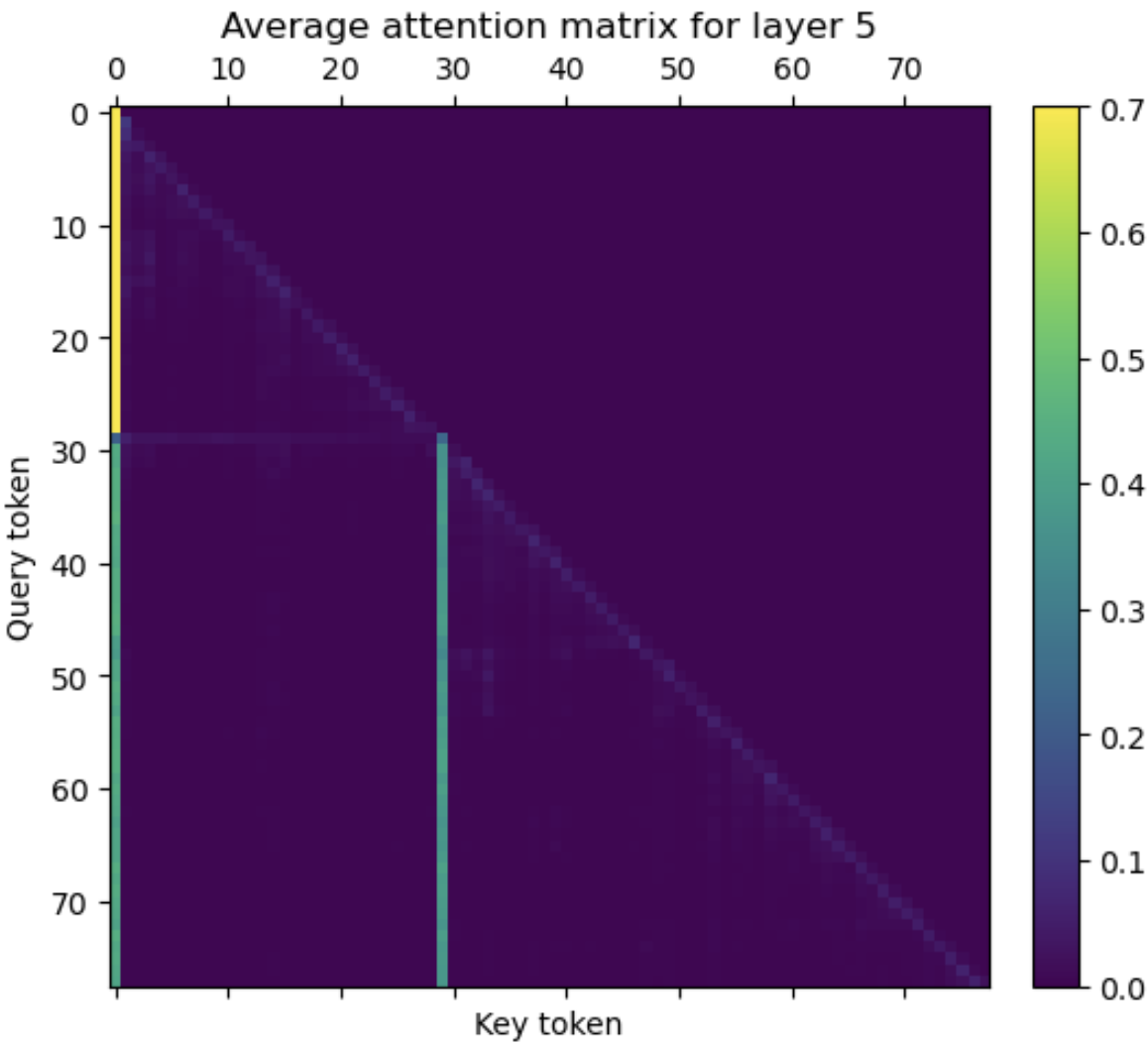

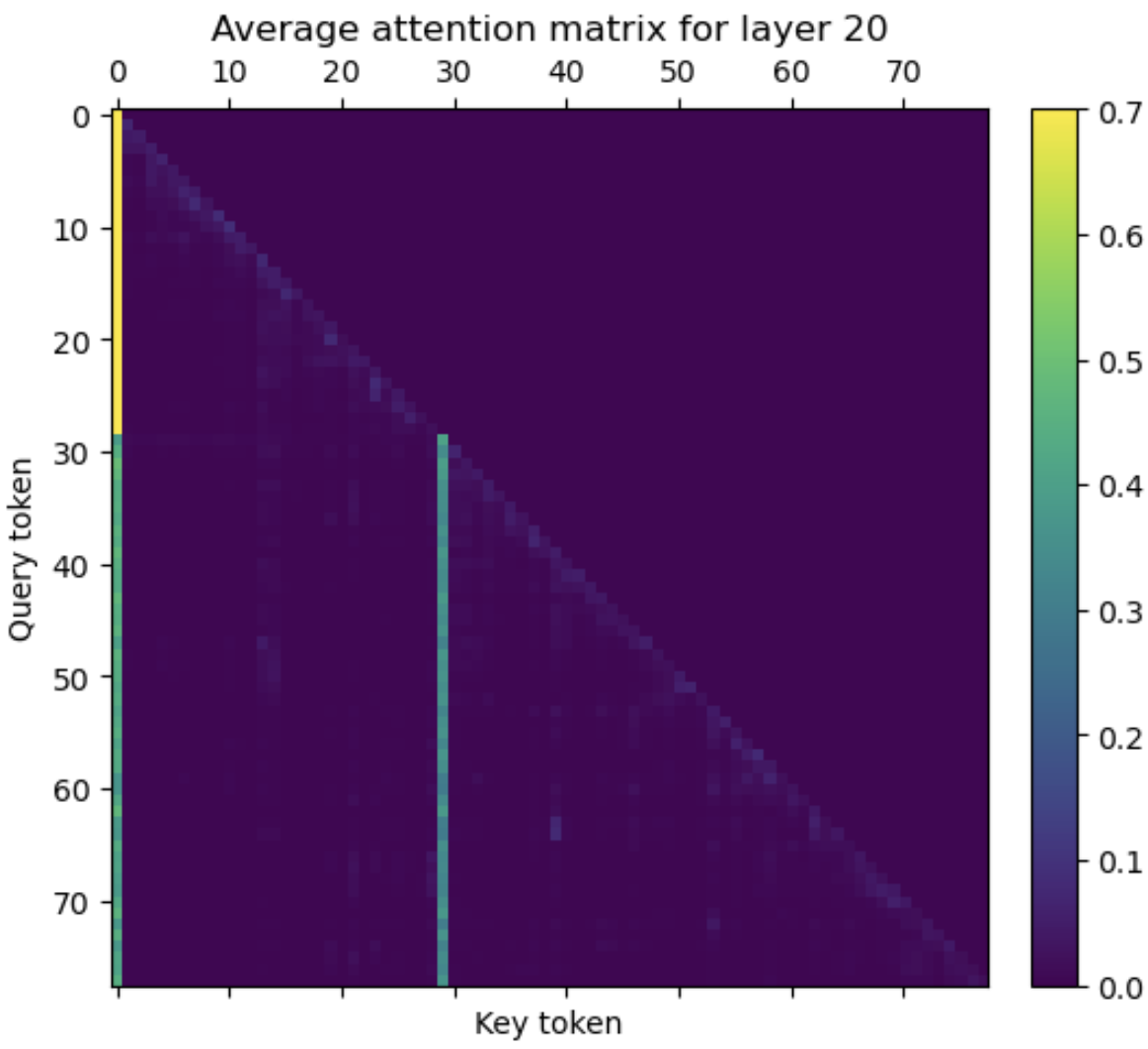

Ready for a surprise? Here’s what a couple of attention matrices for the entire “my_conversation” prompt look like:

Attention matrices for (top) layer 5 and (bottom) layer 20 are averaged over the head axis.

There isn’t just one bright column - there are two. The 30th token (the first “.”) is acting as a second attention sink, receiving attention from every query token that follows it! In fact, the same thing happens for any first sentence termination marker, be it a question mark, exclamation mark, or period. The way this works is that the model has learned convert the first “.”/”?”/”!” token vector into a near-copy of the BOS token vector for the output vectors of the 2nd-30th transformers.

This has an interesting collection of effects and implications:

- To begin with, it highlights the first sentence. Query tokens in the first sentence see only one attention sink, which at the very least will make it easy for the model to distinguish the first sentence from others. This effect was noted in my first post on the Llama 2 model.

-

You would think that adding a second attention sink would cause all attention weights after it to become weaker. As an example: for layer 5, the BOS token accounts for more than 80% of attention weight in the first sentence, and the second sink token has nearly the same attention weight as the first (88%), so from the definition of the softmax normalization, we expect attention values after the second sink to shrink by a factor slightly larger than 1.7 [that’s 1.7 ~ (1.88*0.8+0.2)/(1*0.8+0.2)].

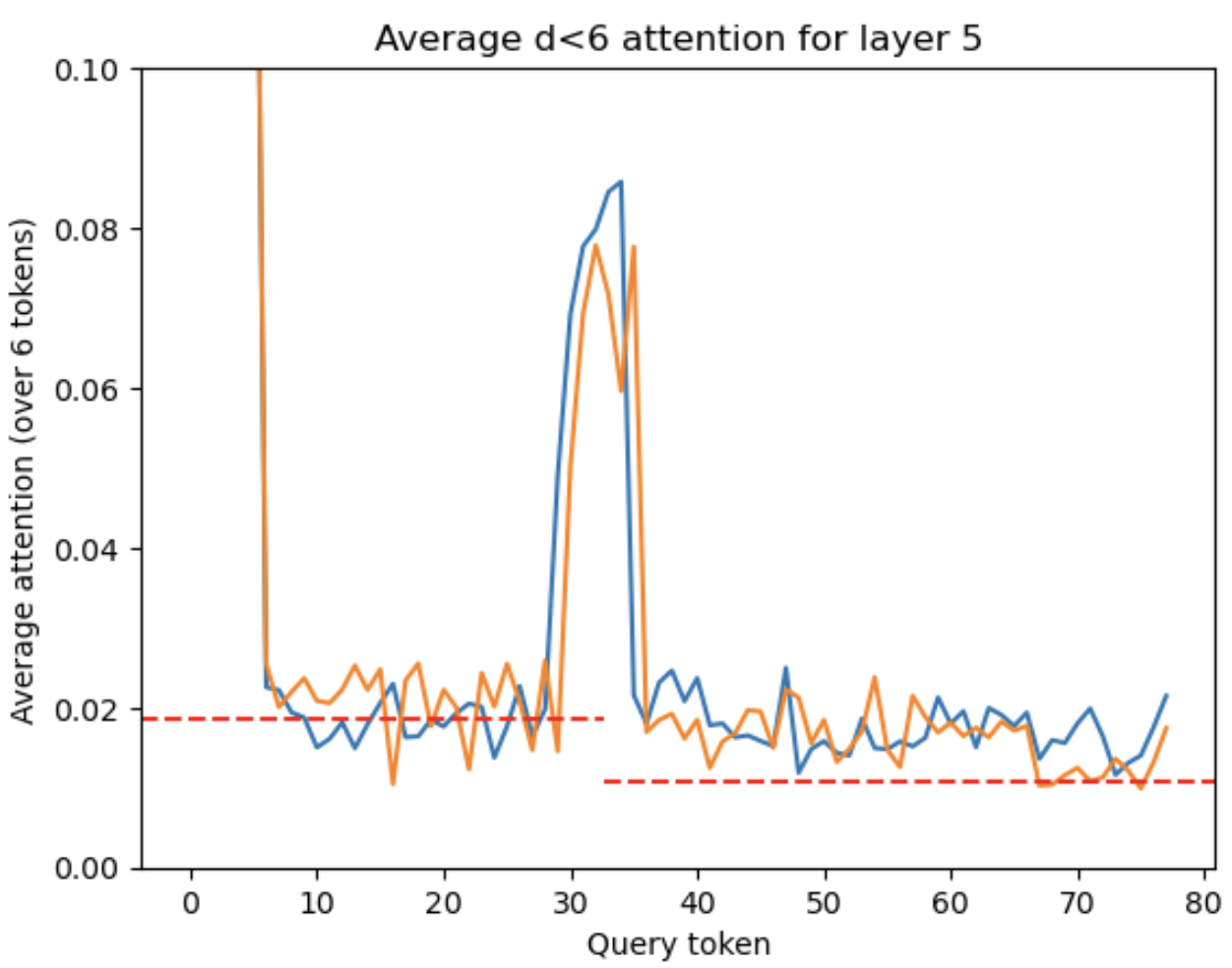

Oddly enough, I don’t see an effect close to this amplitude. The image below shows an example of attention amplitudes before and after the 2nd attention sink using the my_conversation prompt and an unrelated prompt copied from a news article, which has its initial period in about the same place. Avoiding a sudden swing in attention weights seems like an important thing for the stability of the model, and it appears that the model carefully counteracts (most of) this effect of the second sink token. However, the fact that the model would create a second dummy token that every later query couples to, and then carefully strip away that dummy’s effect as an attention sink, suggests that the dummy tokens have additional significance beyond the attention sink effect.

Average attention weight within 5 tokens of the query token in layer 5. The (blue) my_conversation prompt and (orange) news article prompt are overlaid with a dashed line at y=0.0185 on the left and y=0.0185/1.7 on the right, matching the drop that would naively be predicted from the addition of the second sink token.

-

These dummy/sink tokens give the model known vectors that it can incorporate within internal states. Other than these dummy tokens, the model generally has no inputs that can be precisely anticipated a priori. It’s unclear how the model is using these dummy token state vectors, but one can imagine them contributing to the model’s capability to apply ‘internal labeling’ to encoded information.

It’s significant in this context that the 2nd sink token state vectors are not perfect coppies of the BOS token vectors. The 2nd sink token vector converges on the same value (down to about 0.99999 correlation) regardless of the prompt, but differs from the BOS token at a level that is not insignificant to the model. (The L2 norm of the difference between the normalized BOS and 2nd sink vectors is 0.06 ~ (v_BOS-v_sink2).norm()) This strong similarity with BOS makes the two tokens function almost identically as attention sinks, however the difference provides a degree of freedom that may be used to moderate the attention sink effect or apply other labeling.

Take-aways for model design

Time to wrap up!

- My main thrust is that dummy tokens are useful for the model, and that utility probably doesn’t stop at the inclusion of just one BOS token. The cost of adding more dummy tokens seems small compared to the contortions the model needs to go through to create one internally. It could even be prudent to incorporate a collection of them in the training data set, along the lines of my_conversation = “<s1> <s2> <s3> You’re a lovingly crafted, benevolent and superintelligent AI assistant …”

- The attention sink effect is intrinsically unstable – as prompts get longer, the softmax function used to create normalized attention values gains more arguments, and the contribution from the sink tokens will become proportionately smaller. I’m sure that the model takes care of this to some degree, but it may be possible to improve performance in some parts of the context window (for some prompt lengths) by forcing a more constant fractional weighting of the attention sink.

- I’ve said this before, but the amplitude of the attention sink could be manipulated as a prompt engineering tool, to highlight specific sentences to the model.