The Chatbot Architecture of Tomorrow – (3) What Are the Solutions?

“I’m thinking serpentine robot; we go all in on hypermobility.” AI prognostication is like a modern day parable of blind men cybernetically enhancing an elephant. (Image created with DALL·E 3)

This is where it’s all been headed! For each issue highlighted in the last post, I’ll touch on “standard” solutions that are already in widespread use, feasible-but-risky “adventurous” approaches, and “radical” approaches that would be much more drastic to implement.

1. Each token (word part) gets the same amount of ‘thought’.

Standard: A popular tactic is to ask the model to express its reasoning in writing. This technique is termed chain of thought (CoT), and there’s a wide body of literature around it. Chatbots aren’t intrinsically great at this kind of task, and smaller models do particularly poorly, but performance can be improved via fine tuning.

Adventurous: A number of innovative approaches can be found in the literature addressing a broader class of CoT-like solutions, collectively termed “graph of thought” (GoT). As the name evokes, these approaches can allow models to create and traverse mind map bubble diagrams.

Radical: A key difference between artificial and biological neural networks is that biological neural networks do not shy away from cyclical neuronal connectivity and reciprocal connections between ‘modules’ of the brain. One would have to think very carefully before incorporating something of this sort within a transformer stack, but a minimal approach might be to add optionally recursive layers or blocks. As a specific example, one could pass the hidden states output by a selected transformer (say, layer 16) to a perceptron layer with a single yes/no output to determine if the states should be passed forward to the next transformer (layer 17) or backwards for a repeated run of the last few layers (layers 14-16).

2. Tokens are overloaded as RAM.

Standard: Chatbots have a range of emergent tricks for making the most out of the state vectors they’re allocated, such as loading frequently referenced constants and (it appears) sentence summaries into the hidden state vectors of punctuation tokens, such as periods. The distinctive ML-identified prompts that optimize CoT performance for specific models probably interact constructively with this form of memory management.

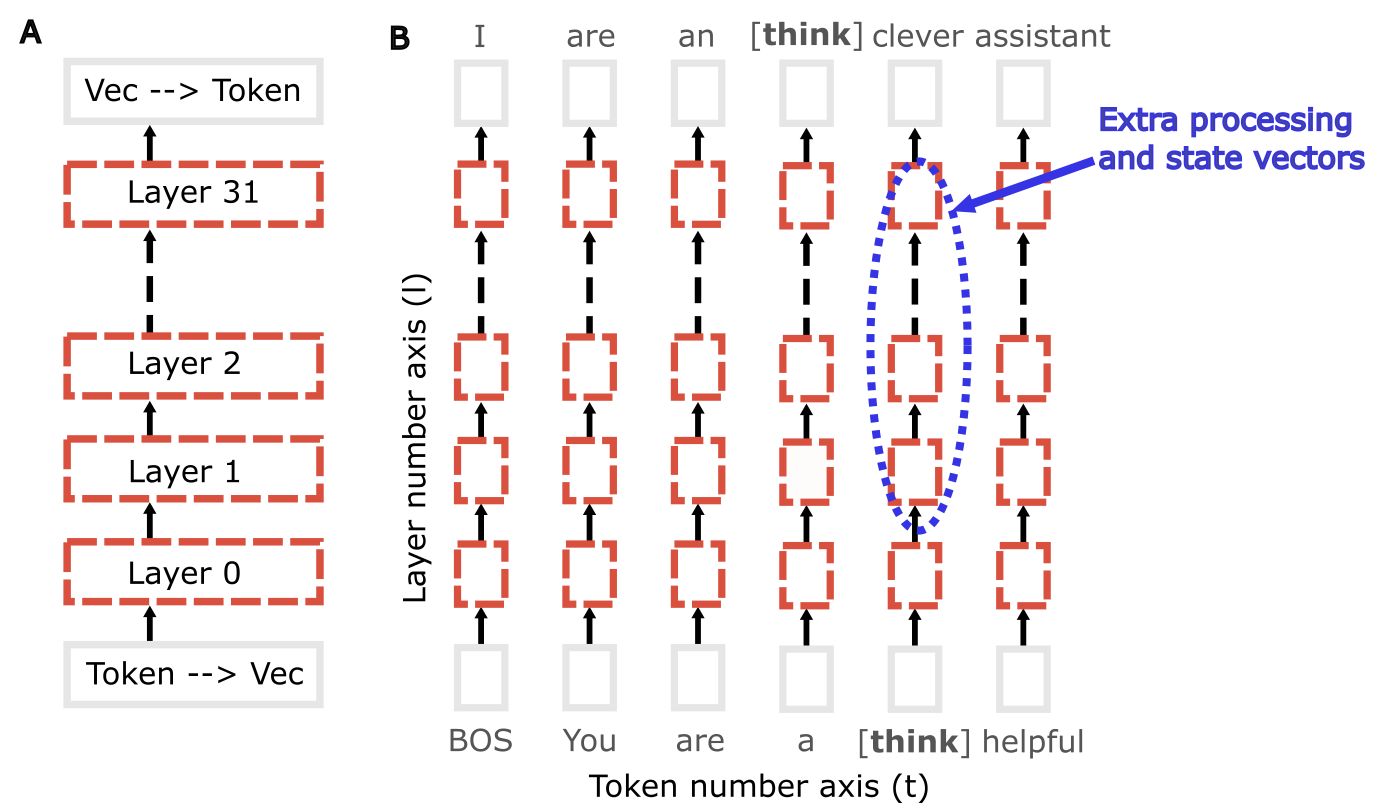

Adventurous: One could potentially try to mitigate these memory and ‘thinking time’ bottlenecks by adding a new class of padding token that I’ll term a ‘thinking token’ to the model’s vocabulary. Thinking tokens would exist purely to allow the model to allocate an additional set of state vectors, and would not be considered in perplexity calculations so long as the chatbot used them infrequently (say, <10% frequency):

Architecture schematic with a ‘thinking token’. Words proposed by the model are shown at the top of panel (B). As the model is reading a user-provided prompt, only the [think] token is entered into the input text stream, where it results in the creation of an extra set of state vectors.

This would go a (very) small step towards making models function as a persistent awareness – akin to human consciousness.

Radical: It would be easy to add extra sets of LSTM-like memory states that are passed forward along the token axis and communicate with selected transformer layers within the chatbot model. Plausible designs in this broader class have been explored, so there are probably good reasons that we’re not seeing them incorporated in the latest open models.

3. Models have no long-term memory.

Standard: The default answer to this is to apply some form of retrieval augmented generation (RAG), which amounts to giving the model access to a search engine. One can also train the model on content that you want it to ‘memorize’, but this opens up several cans of worms, and tends to be a better fit for skill and alignment training than knowledge acquisition. It’s common to liken RAG to single-step fine tuning within the literature, but the two are not the same. For example, in context learning does not suffer from the reversal curse, in which a chatbot that has been exposed to an A–>B relationship during training (say, “Hexaquarks are six-quark particles”) is able to answer “What is A?” (“What is a hexaquark?”) but will often fail to answer questions about the reverse relationship (“What would you call a six-quark particle?”).

Adventurous: There are a lot of fascinating ideas floating around right now! Using an auxiliary AI model to organize archived information in a knowledge graph (KG-RAG) can enable superior associative memory, though at a cost in complexity (computational and otherwise). Alternatively, one can take things in the opposite direction and use the base chatbot model for everything. This is the unliformer/multistate RNN approach, which uses the base chatbot model to encode archived information as hidden state vectors, and then co-opts the key/query attention mechanism as a search engine to identify relevant content outside of a conventional context window.

Radical: It would be exciting to have a model that could form long term memories within its own ‘brain’ (the model parameters), rather than needing to log them in an external database and pull them up with a search engine. If we look to biological brains for inspiration, a couple of elements that stand out are: (1) the ability to convert neural activity into memory without full backpropagation; and (2) integration of context and the experiential process of learning within memory. The chatbot should be able to recall the context in which learning occurred and have some impression of its own concurrent thoughts.

Another way to frame this is that we want to convert the short term memory that language models exhibit during conversations, termed “in context learning”, into an update to parameter weights. This looks promising at first glance. Several recent papers have established a strong similarity between in context learning and gradient descent parameter optimization. One can define a matrix that represents in context learning for a given attention head (for example, “ΔWICL” in this paper) and use it as a learning target, but the devil is always in the details for a real engineering challenge like this.

For example: ΔWICL is relatively low-dimensional, and leaves the parameter update underspecified; the update may be difficult to harmonize with positional encoding; we no longer have explicit coupling to an output based loss function such as perplexity or RLHF; and parameter updates may lead to instability or catastrophic forgetting, which is something that even humans undergo in the form of childhood amnesia.

Having a fluid exchange between long and short term memory also frees the brain from needing to constantly reference thousands of words within a ‘context window’ of immediate working memory. In fact, human immediate memory has a persistence of less than 1 minute, beyond which information needs to be maintained through longer term storage or active rehearsal. This naively corresponds to context window of just ~100 words, if you factor in the typical speed of speech.

A model with this capability would have a different relationship with its training data. In context learning involves kinds of free association that standard model training does not – for example, it does not suffer from the reversal curse. An optimistic take is that such a model might require far less training data, akin to human learning which tends to require relatively few examples. We can thank SMBC for a less optimistic interpretation of this particular gedanken experiment:

4. Attention layers are pattern matching tools:

Standard: The obvious band-aid is fine tuning. All current chatbots receive specialized training on data sets that promote cognitive skills such as attention span (see Llama 2 ‘ghost attention’) and domain-specific chain of thought reasoning. However, the degree to which this ‘reasoning’ proficiency transfers between domains can be limited.

At an architectural level, if the attention sublayer is a poor basis for ‘cognition’, it would make sense to focus instead on the general purpose feedforward sublayer that constitutes the other half of a transformer. This is exactly what has happened. The Llama family of open source chatbot models added a 3rd matrix (GLU activation) to the feedforward layer, and the strongest open model at the time of writing, Mixtral-8x7b, expands the feedforward parameter count by a further factor of 8. Feedforward networks are well suited to applying logic gates and mapping out conditional relationships. The feedforward networks of consecutive layers can (in principle) work together to deliver the versatility of a deep multilayer perceptron network.

Adventurous: Multi-agent systems (MAS) are a hot topic in AI and have the potential to become much hotter. These systems often assign several chatbot agents to function as competing debaters, and can do well relative to naïve zero-shot chain of thought prompting. A long term question is whether the agent roles can ultimately be expanded to function as an entirely different collective entity. As limitations on reasoning and long-term memory are pushed back, one can imagine the formation of companies in which all or most employee roles are taken on by AI. One can also imagine that this would be a sufficient and perhaps necessary condition for the Robot Apocalypse – Chatbot Edition.

Radical: If feedforward sublayers provide a part of the solution, then there are endless ways to expand them, expand their connectivity within the transformer stack, or to couple in auxiliary neural networks – akin to the reciprocal synaptic connections between different areas in the human brain. Of course, most approaches of this sort would violate the architectural principle of simplicity that has dominated transformer-based AI development.

5. Chatbots are required to overthink things.

Standard: Once again, training is the main way to address this issue. Ensuring that questions in the training data are answered correctly and use well-constructed chains of thought (CoT) also helps keep the model focused on the right things. Nonetheless, it’s very challenging to align chatbots with human goals.

Adventurous: One can train models to navigate mind maps (graph of thought, GoT), as noted in item #1 above. Framing a problem in terms of a mind map can force a chatbot to focus more closely on one line of reasoning at a time.

Radical: If you want a chatbot can think in an organized way, the best human-inspired approach may be to have it remember and consciously develop its own creative process, as considered in the “radical” section of item #3 above.

6. Chatbots are energy-inefficient problem solvers.

Standard: There’s a lot of room to distill (or otherwise engineer) capabilities of larger models into much smaller models, such as for translation, simple conversation, or navigating app interfaces. The Rabbit R1 seems to embody this approach more than any other product right now, and squeezes a wide range of multimodal AI capabilities into a $200 package with far too little computing power to run a top-of-the-line language model.

Adventurous: If emulating chatbots on digital computing devices is too expensive, how about creating analog computers that can run your AI natively?! As it happens, there’s an entire field of engineering devoted to the exploration of these ‘neuromorphic’ analog computing technologies, and I’ve seen a number of fascinating approaches to the problem over the years. The stakes motivating this class of innovation are higher than ever, and companies like Lightmatter will be fascinating to follow over the coming decade. One should bear in mind however that the AI architectures we use on digital computers are likely to be far from optimal for natively analog systems.

Radical: Sam Altman and others have recently drawn attention towards fusion power as a potential mitigating factor. Exciting breakthroughs over the last decade seem poised to allow stable fusion power generation to be achieved in the next few years. The world could really use a new clean and abundant power source, but it will take a while to see where the current technological push can really get us as far as the stability, maintenance costs, and overall practicality of fusion power facilities. For example, quenches (sudden failures) of the superconducting magnet that contains a fusion reaction can release energy comparable to 1000 kg of TNT and may be difficult to avoid due to progressive radiation damage.

7. Chatbots will face regulatory scrutiny. (policy architecture!)

This series of posts is focused on the technical side of things, so I won’t try to do justice to AI policy. (Maybe some other time? I’d love to exchange thoughts in person!) We’re already seeing the shadow of human-like AI in union contract negotiations and new laws that regulate the use and capabilities of AI. I’m sure this is just the beginning, and I’m just as sure that, to some extent, the genie is out of the bottle.